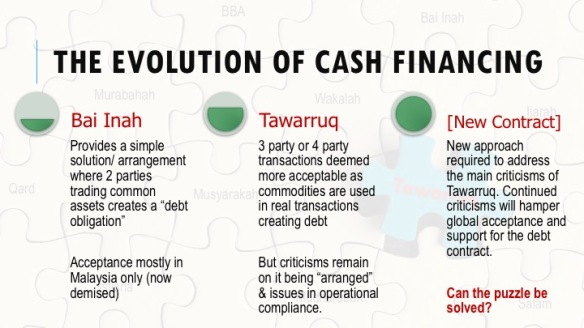

I have been asked recently on the validity on a Bai Al Inah contract that had sparked controversies many years ago by claims that it is not a valid Islamic contract that is rejected by most Shariah scholars.

I have been asked recently on the validity on a Bai Al Inah contract that had sparked controversies many years ago by claims that it is not a valid Islamic contract that is rejected by most Shariah scholars.

What do I think? As limited my Shariah knowledge is, the position of Bai Al Inah, and its counterpart Bai Bithaman Ajil (BBA), have always been that it is a structure of 2 standalone contracts of Musawamah (simple sale) and Murabahah (deferred cost-plus sale). The intention of these 2 contracts is for the purpose of obtaining cash or working capital through creation of debt. Both contracts are executed consequentially and valid as all the tenets of the contracts are met perfectly.

SO WHAT IS THE ISSUE THEN?

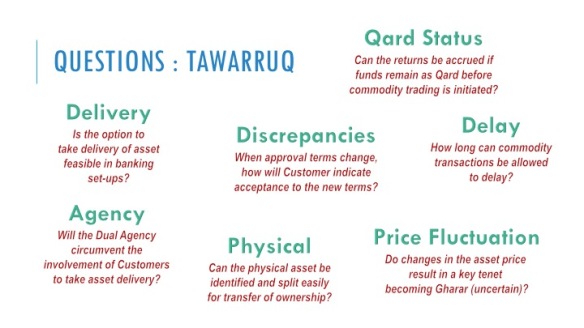

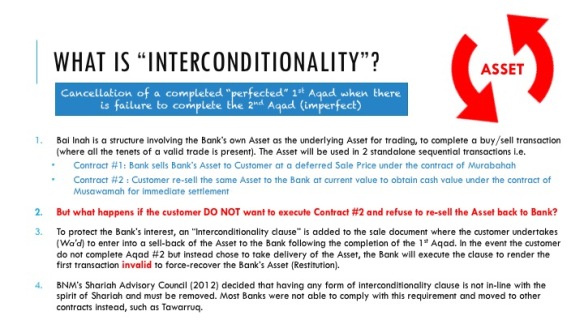

Generally both contracts of BBA and Bai Al Inah suffers from the same issue ie the existence of “Interconditionality” practices in their legal clauses in transaction documents. Both contracts have 2 standalone contracts i.e. one sale contract and one buy-back contract. Both contracts must be able to stand alone and the aqad is executed sequentially, which makes it valid based on trading rules.

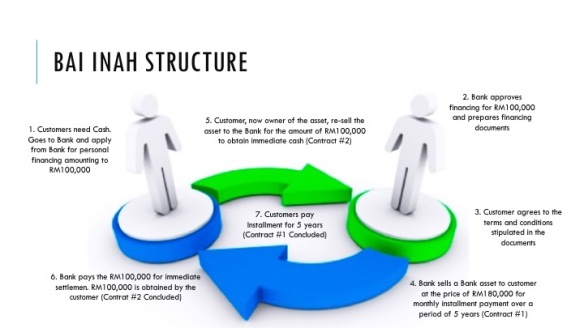

The Aqad for the Bai Al Inah transaction uses the Bank’s own Assets for the underlying transaction, as the customer do not have any Asset to sell to the Bank in the first place. So Banks have been using their own Assets such as pieces of land, office hardware, office furnitures, company shares, investments in securities, machines, and any other valuable Assets that is identifiable, transferable and valuable.

CONTRACT #1 – SALE OF BANK’S ASSET (MURABAHAH) TO CUSTOMER IN BAL AL INAH

These Assets are to be sold by the Bank to the Customer at a Sale Price (includes profit) and to be settled at a later date or at specific intervals. For example, the Bank sold its ATM equipment to the Customer at a price of RM180,000. This amount is to be paid back within 5 years (Deferred). This is a valid and perfected standalone contract. The debt created here remains valid until full settlement at the end of the 5th year.

CONTRACT #2 – BUY-BACK OF BANK’S ASSET (MUSAWAMAH) FROM CUSTOMER IN BAL AL INAH

The Bank then makes an offer to Buy-Back the Bank’s Asset from the Customer at a simple sale transaction where the amount will be settled immediately. As the Customer intention is to obtain Cash or Working Capital, the Customer will generally agree to the Bank’s offer to Buy-Back the Asset at the current market price. For example, the Bank offers to buy-back the ATM equipment from the Customer at a price of RM100,000. This amount is to be paid immediately for settlement. Bank takes ownership of the ATM and pays the Customer RM100,000 cash. This is also a valid and perfected standalone contract

BUT WHAT HAPPENS IF THE CUSTOMER, AFTER COMPLETING CONTRACT #1, REFUSE TO ENTER INTO CONTRACT #2 AND DECIDE TO KEEP/TAKE THE DELIVERY OF THE ATM EQUIPMENT INSTEAD? THIS REPRESENTS A RISK TO THE BANK AS THE ASSET (ATM EQUIPMENT) IS NOW RIGHTFULLY OWNED BY THE CUSTOMER UPON COMPLETION OF CONTRACT #1

BUT WHAT HAPPENS IF THE CUSTOMER, AFTER COMPLETING CONTRACT #1, REFUSE TO ENTER INTO CONTRACT #2 AND DECIDE TO KEEP/TAKE THE DELIVERY OF THE ATM EQUIPMENT INSTEAD? THIS REPRESENTS A RISK TO THE BANK AS THE ASSET (ATM EQUIPMENT) IS NOW RIGHTFULLY OWNED BY THE CUSTOMER UPON COMPLETION OF CONTRACT #1

Because banks want to minimise risks, the interconditionality clauses are added to ENSURE that once the first sale contract (#1) is concluded, the second buy-back contract (#2) MUST be executed (mandatory). It goes on to say that if the second buy-back contract is not executed, then the first sale contract is invalid and restitution (going back to the original state) must be effected to recover the Asset already sold; in this case the ATM Equipment.

From Shariah point of view, it is problematic, because the first Aqad for the sale contract (#1), is a valid contract and completed under Aqad which meets all its trading tenets. To impose that another external event (i.e. the non-completion of the buy-back contract) that will invalidate a valid sale contract (already concluded and perfected), implies that the whole arrangement is superficial and do not carry real value.

This must not be the case, because the Aqad is already validly executed and is now running. Thus having the interconditional clauses is not favoured by Shariah and needs to be removed.

In Summary:

1) The Sale of Asset contract is valid on completion of Aqad

2) The Buy-Back of Asset contract is valid on completion of Aqad

3) If the Buy-Back of Asset contract (#2) is not completed, the Sale of Asset (#1) remains valid as the Aqad is already completed.

4) The requirement to force the Buy-Back of Asset contract to be completed via an interconditionality clause is problematic in substance. The notion of “one contract is only valid upon completion of another contract” does not sit well with Shariah.

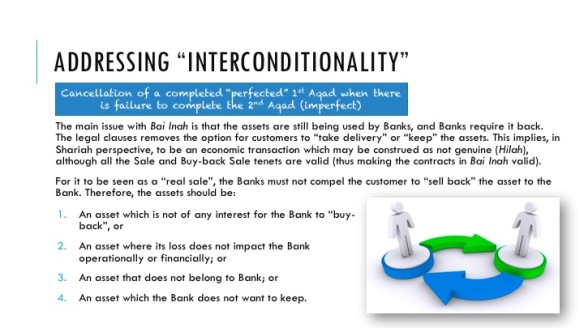

Of course, for Banks, removal of such clauses from the documents represents a risk as the assets used for the transaction belongs to the Bank in the first place. The idea that the Customer cannot be compelled / forced to re-sell the assets back to the bank (or banks not allowed to buy-back) is a risk banks are not willing to take. As such impasse, the only way most banks can comply with the requirements to remove interconditionality in their contracts is to remove these contracts from their shelves.

There are still some Banks using products based on BBA or Bai Al Inah, but such usage is now limited to its uses are required by design (such as restructuring an existing Bai Al Inah account) and/or mainly transactions between financial institutions (not between banks and retail consumers) where the interconditionality clauses are not required/ can be ignored.

For the public, Tawarruq or Musyarakah Mutanaqisah or Ujrah structures are now used as acceptable replacements of both Bai Al Inah and BBA products, signalling the demise of these hugely unpopular products.

Wallahualam.

It is an interesting situation in Malaysia now, when it comes to food. In general, Malaysia as a Muslim country, the expectation is that the food consumed must be Halal and more importantly certified as such. The reason for it is that it gives comfort to the public that certain standards are adhered to according to religious requirements. To walk into a restaurant with the Halal signage gives us Muslims confidence to consume the food till our bellies are filled.

It is an interesting situation in Malaysia now, when it comes to food. In general, Malaysia as a Muslim country, the expectation is that the food consumed must be Halal and more importantly certified as such. The reason for it is that it gives comfort to the public that certain standards are adhered to according to religious requirements. To walk into a restaurant with the Halal signage gives us Muslims confidence to consume the food till our bellies are filled.