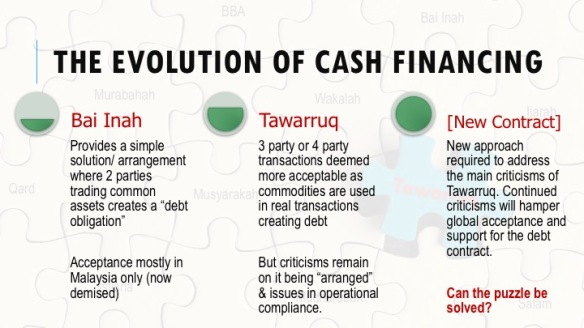

Islamic Banking in Malaysia is fast reaching a crossroad. While Islamic Banking continues to offer like-to-like conventional structures, the requirements by Shariah Committees and Policy Documents by Bank Negara Malaysia continues to challenge the way Islamic Banks implement and operationalise the products within a viable banking structure. Islamic Banks are becoming mindful of the need to comply fully to each policy requirements.

It is precisely this fear of being “non-compliant” to these requirements that pushes many Islamic Banks to develop the Tawarruq-based products into its most efficient form. As I have written earlier in Disruption : Islamic Contracts where I felt the Tawarruq arrangements has become the “go to” structure that Islamic Banks can easily comply with, the notion that other contracts such as Musyarakah or Ijarah or Mudharabah may now be left behind in its development due to perceived complexities. Or in some cases, difficulty to comply due to the existing banking set-up, especially in matters of risks, capital and operational processes which is intrinsically based on conventional banking infrastructure.

BUT CAN TAWARRUQ ALWAYS BE THE ANSWER?

It is generally accepted that a lot of processes in the Tawarruq arrangement can be complied with. There were strong operational support and infrastructure both internal and external, such as the London Metal Exchange (LME) and Bursa Suq Al Sila which has an efficient commodity platform specifically designed to support Tawarruq with or without commodity brokers, to the choice structure that bridges the middle-east players to most of the rest of the Islamic Banking geographies. But that is by no means that Tawarruq is a perfect solution for Banks.

Despite Tawarruq is now greatly used over the last decade or so, there are still contention points that remains amongst financial practitioners and Shariah scholars. Most scholars want to have the view that Tawarruq should be the “contract of last-resort” but what we see now are quite the opposite. It is the preferred choice being used not just for Working Capital requirements, but now also for Asset Financing, Mortgages, Trade Financing, Fixed Deposits, Structured Investments, and even Savings Account. Whenever an Islamic Bank hits a roadblock with a particular product being developed or requiring compliance to the latest rules, the tendency is always to consider Tawarruq as the solution.

If this is the approach, how much do we really need other Islamic contracts which only addresses a single problem or requirement? Shouldn’t we develop Tawarruq as far as it can take us and make other contracts as “supporting” contract to cater for specific nuances?

THE UNANSWERED QUESTIONS ON TAWARRUQ

Each year when Bank Negara Malaysia audit comes around, there will always be new compliance points to be proven and tested. Even at the level of understanding and interpreting the Policy Documents into processes and banking operations. Each Bank interprets the rules differently, and each banking set-up have different operational capabilities which more often than not, requires exceptional Shariah indulgence. So, the questions will remain unanswered whenever dispensation is obtained.

Many argue that the main issue of Tawarruq is actually the “intention” of the contract itself, and that intention is not to “trade in commodities” but to create debt via a trading transaction. This has been debated at length for many years in all types of forum, but we concede on some of the arguments by virtue of there being no other viable solution to cater for certain banking requirements. Islamic Banks, and its scholars, had to choose either:

- Allowing for the Tawarruq arrangement with strict adherence to requirements until a solution arrives, or

- Disallowing the Tawarruq arrangement which may result in customers being impaired in their Islamic business, which may result in the customer reverting to a conventional banking solution.

Is there a case of choosing the lesser of two evils?

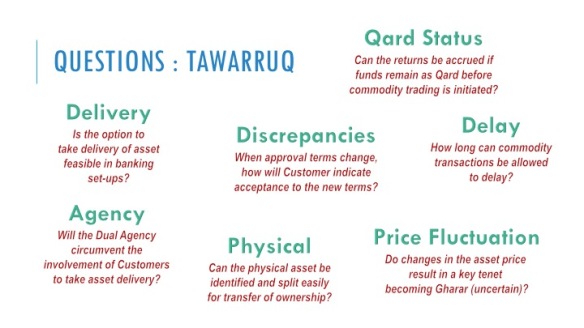

Nonetheless, I won’t discourse what have been extensively discussed, but instead look at the operational issues of Tawarruq arrangements that I pick up going through the Tawarruq Policy Document. Among them that are still being debated in different forums are:

- The issue of Commodity Delivery – To demonstrate that the Tawarruq being practised by the Bank is real, the test of delivery of Commodity is a key qualifying factor. The Bank must have in place a mechanism that allows the customer an option to take delivery of the commodity whenever the customer calls for it, bearing in mind that may have not been the intention in the first place i.e. taking delivery of commodities. How a Bank prove this to Shariah Committee and regulators are crucial to demonstrate “real transaction” and paper transactions.

- The issue of Price Fluctuation – Depending on commodities, its price tend to fluctuate periodically, because these are actual live commodities being traded. Because of this, Banks have not been able to be precise in its documentation or price disclosures. Whatever price per commodity unit at 10am, it might change at 2pm, so how do you lock-in a specific price when the buy and sell of the commodity was not concluded immediately? The fact that Bursa Suq Al Sila states in its guidance notes that an Islamic Bank could not hold the commodities for more than 2 hours implies the issue of price fluctuation is a valid concern for Shariah Committees.

- The issue of Discrepancies of Terms – Because the Murabahah transaction in the Tawarruq arrangement is the most crucial contract, Scholars always insist on the details of the transaction to be as precise as possible to ensure what was offered was eventually rightly accepted. For example in a Personal Financing structure, the customer makes a credit application according to certain terms such as financing amount, or financing tenure, but what eventually gets approved might be a lesser amount or shorter tenure, which means differences in the initial “Agency” instruction to transact the commodity. Scholars question how do Banks re-engage customers with such “counter-offer” for their acceptance? At which point after the credit approval?

- The issue of Delay in Transactions – Some banks are more efficient than others. Some banks are able to conduct commodity trading on the same day while others can only do it in the next day after the day’s batch run. End of day batch runs are what conventional banking live by, and there is no motivation to conclude and consolidate all transaction in real-time; there is no requirements to do so. Batch runs allows for more systematic consolidation of records. But that becomes an issue for Islamic banks running next to a conventional banking proposition. So if an Islamic bank is limited to only end of day batch run to consolidate its records, it means the end of week transactions requirements will only be fulfilled on the next working day (across the weekend). This is a delay in the conclusion of the initial instruction given by customer to conduct Murabahah which may impact specific terms including price of commodity and its availability. There is also the danger of missing out delayed transactions as those instructions are not “current” anymore. There is a provision in the Policy Documents that “delay” in transaction should not be more than 2 days (T+2), but there are also periods where the off-days are more than that due to public holidays and other disruptions.

- The issue of Qard in Tawarruq – An extension of the above scenario where Commodity transactions are delayed, the next question will be “what is the status of the funds when no transaction is done?” Is it a Qard (Loan) contract until the transaction is fulfilled, or is it an Amanah (Trust) arrangement? In either case, for the scenario of Tawarruq Deposits, how do you accrue the profit for both contracts which forbids “interest” or “returns“? Profit is only realised once the Murabahah (trade) takes place. Without the trade being transacted, profit accruals can only be justified by arguing that Islamic banks should not penalise customers who, in this case, has done nothing wrong. Dispensation is always given for the reason of fairness. And this “Incidental Qard” issue has also been discussed at the Shariah Advisory Council of Bank Negara Malaysia, where the fatwa on Incidental Qard and its conditions were issued. But the fact that it was discussed, indicated that this issue is not as easily brushed aside as one like to think.

- The issue of Agency and Dual Agency – There are still some banks that feels the Dual Agency structure contributes greatly to the notion of “arranged” Tawarruq and thus stays away from it. The Dual Agency structure is where the customer appoints the Bank as both the Buying Agent and Selling Agent. This gives the Bank the full right to conduct trading without any Customer intervention (given mandate), which makes the “ability or option to take delivery of commodity” redundant or unnecessary requirement. It effectively removes the proof of Murabahah i.e. deliverability of the Commodity.

- The issue of Physical Commodity – One of the main contention is the ability to ascertain the availability of Commodity. While on paper it can be evidenced but nonetheless the challenge is to ensure the Commodity is identifiable and deliverable according to quantity. Efforts have been made to split into smaller denominations whenever needed, and commodities like Crude Palm Oil (CPO) is easier to be allocated. But there is always suspicion whether this is superficial where proof of otherwise is actually much more difficult to obtain. Where is the certainty that the assets being traded are the right physical ones?

THE REAL QUESTION IS WHETHER THE ABOVE CAN REALLY BE RESOLVED

So is there any other alternatives to Tawarruq? The above questions have so far not been answered satisfactorily and scholars while do not prohibit its usage, still frown on how much Tawarruq has impacted everyday banking life. It is truly a “love/hate relationship,

I believe there is such “replacement” contract that can address most, if not all, of the above concerns. But it needed to be proofed and challenged and at the end of the day, we question such necessity and thus the rising dilemma to replace it after all the work done. Tawarruq has really taken root with so much invested in perfecting the structure, and expertise in its documents and mechanism. It solves a lot of problems, yes. But will Tawarruq be the end of innovation for Islamic Banking?

I like to think there must life beyond Tawarruq. It just needed courage to acknowledge the big task required for such massive structural changes in replacing Tawarruq. Such replacement must not just be an equal substitute but also addresses the Shariah concerns. That is the ultimate test of any Islamic Banking contract; the reason for being.