IS THERE SUCH A THING AS ISLAMIC RISK MANAGEMENT?

I had this conversation recently until the wee hours of morning, and although I never thought a lot about it, I have come to the conclusion that there cannot be an exact replica of the Risk Management in the conventional sense.

Risk Management is a tool used by all conventional banking institution in the name of good governance, risk mitigation and prudent practice. It looks at financial exposures and its inherent risks to the business, and deeply believe in the risk-rewards pay-off within the generally accepted risk appetite of the organisation. It focuses a lot on control processes, performance monitoring, collateral value, and decision making policies for credit, market and systemic risks.

To a large extend, the risk management framework employed by the conventional banking businesses can be easily adapted by Islamic Banking counterparts. The components are the same, and there is little argument on its applicability under Shariah law. However, the risk management framework for Islamic Banking institutions must be inherently different as well, or maybe extended to include a bigger scope. It cannot just be seen as a replica of the conventional business; the foundation of Islamic Banking is definitely different.

There are a few divergence in the reason an Islamic Banking institutions should (ideally) follow. This is an on-going argument on the fact while Islamic Banking claims to be a different business model, but it is still engineered by the rules of a conventional organisation. But what are these divergent reasons for setting up an Islamic Banking business?

The lending of money to make money is forbidden.

This may seem like a trivial thing for Islamic Banking as many will say there is no difference between profit and interest. But for us practitioners, there is a big difference in its concept. Because of this difference, the way we think about how a product can be structured is paramount. Underlying contracts, assets, ownerships and roles and responsibilities becomes different from a tranditional / conventional bank (whom are essentially a money lender). To validate a transaction, all tenets and requirements in an Islamic contracts must be met or else it becomes an invalid transaction and any gains from it must be given to charity. Any gains obtained without fulfilling the transactional can be deemed as usury (riba’).

There are specific Shariah requirements that takes Islamic Banking beyond banking.

Some terms are pretty alien to traditional banks, such as commodity purchase, operating lease and rentals, sequencing and ownerships. This is where the divergent begins, because Islamic Banks espouses the concept of “trading” and “entrepreneurship” and “partnership” and “service provider”, away from the “lender-borrower” arrangement. Traditional banks struggle to understand issues of ownership of assets, risk and loss sharing, purchases of commodity and rental of assets. These activities are beyond traditional banking, and may become an operational risk issue if it is not fully embraced.

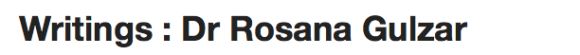

Islamic Banking should be more closer to a venture-capitalist, crowd-funding model than traditional banking.

The fundamental requirements for earning a profit (and to a bigger extent, how much we can earn from a transaction) is the element of risk sharing, which mean both customer and financier takes some form of the risks of the venture. At the same time, such “risky” venture is mitigated by way of ensuring it is not overstretched i.e. the transactions must be either asset-backed (including the presence of collaterals) or asset-based (evidenced by real trading or assets or commodities) to reflect economic activity.

The amount of risk taken under an Islamic contract can be higher (for contracts such as Mudharabah or Musyaraka financing) but it must be reflective of the economic reality and available assets.

The risk assessment of an Islamic contract must then be enhanced to behave similarly to what a venture capitalist can accept. There will be direct risks on equity, investments and returns. There will be corresponding returns as well. But such concepts will be difficult to digest if the bank is set up based on traditional banking fundamentals, which caters for a totally different profile of stakeholders.

As far as possible, the Shariah committee draws a line for transparency, fairness, and justice.

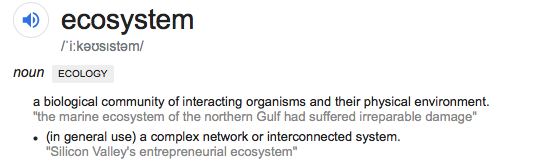

Islamic Banking should be an extended but integral part of economics. Islamic Banking is supposed to be more than a bank. It shoulders a broader responsibility to the people by looking at needs and providing products that serve a purpose. The idea of responsible financing, transparency and customer service should be the by-word of an Islamic Bank. The payment of Zakat (tithe) on profits which goes back into the community recognises the financial role that it needs to play. Corporate Social Responsibilities also play a role.

In this repect, the Shariah committee plays an important role as gatekeepers to the products and services on offer. Because of the unfamiliar territory of Islamic products, Shariah insists that transparency is critical to avoid uncertainty (gharar), the terms to the products are fair and the banks are ethical in its conduct to ensure justice. Fees and charges must reflect actual costs. Efforts are made to help a customer in distress. And conduct of the bank must comply with the requirements of Shariah.

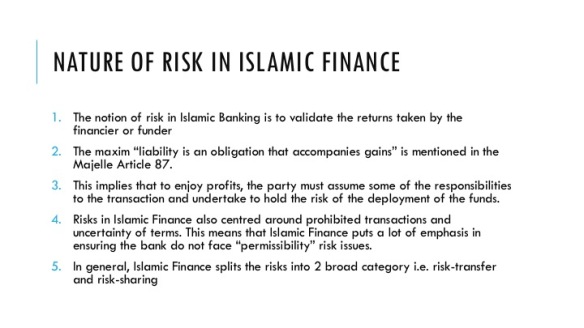

SO, BASED ON THE ABOVE, WHAT ARE THE OF RISKS FACED BY ISLAMIC BANKS?

As a general rule, all risks faced by a conventional Bank must be “transferable” i.e the nature of the financial transaction must, as far as possible, allow for the TRANSFER OF RISKS. Wherever the opportunity arises, the Bank must be able to quickly pass the risk of the asset or valuation to the customer. Such understanding is also apparent in Islamic Banks. Looking at most Islamic Banking contracts, their structure allows for the transfer of risks, which follows the transfers of ownership, responsibilities and obligations from one party to the other. Contracts such as Murabahah, Musawamah and Qard works by transferring the ownership, responsibilities and obligation from the Bank to the Customer.

Alternatively, mostly exclusive to Islamic Banks, are structures that allows for SHARING OF RISKS. The structure is more “participative” in nature, where there are benchmark by which determines the level of risks a party should have. The regular types of contracts that continues to share risks are Mudarabah, Musyarakah and Ijarah.

COMMON RISKS

As mentioned before, the risks faced by a conventional bank and Islamic Bank should be very much the same, except for risks arising to the execution of Islamic contracts or pronouncement of the Shariah. While there will be common elements of risks for both types of Banks, the importance of Shariah ruling and decisions result in Islamic Banking becoming so unique. The following are the Risks commonly faced by Islamic Banks:

GENERAL RISKS – Risks existing in both conventional and Islamic banks.

- Credit Risks – Arises due to counterparty risks (possibility of default by the party taking financing) where the counterparty fails to meet its obligations, in terms of payment, uncertainty of industry, change of direction or diminished collateral value. This lead to settlement risks which means the Asset quality has diminished.

- Market Risks / Interest Rate Risks – More macro in terms of effect on the risks. It relies on the performance of the market as well as the quality of the financial instruments (price, performance, valuation, demand, yields and inability to reprice. It leads to exposure to interest rate risks, where the risk of the bank increases with movements in the rates.

- Liquidity Risks – Refers to the risk of inability to return cash to investors or stakeholder in stressed scenarios, resulting in forced borrowings from the market (usually at higher price) coupled with the possibility of not able to dispose assets. This may lead to valuation risks.

- Operational Risks – Due to inadequate control of internal processes and operational practices, the risks may result in real loss of income and potentially reputation. Human errors may be difficult to unwind especially if there is financial implications. There may also be legal risks as it may be considered a breach in contract by the bank.

ISLAMIC SPECIFIC RISKS – Risks arising from operational and processing function

- Transactional risks – Especially under Islamic Banking structures, transactions play an important role as part of the Aqad, where required. For example, the sequencing of a Murabahah transaction. Failure to ensure compliance to the Aqad requirements will lead to potential invalid transaction and loss of income (or flow to charity).

- Valuation Risks – Due to the nature of some Islamic Banking contracts, especially equity based structures, there will be challenges in valuation of the portfolio. Reduction in valuation will result in real losses for the investors.

- Displaced Commercial Risks – Displaced Commercial Risk (DCR) refer to the risk of mismatch between the fixed/contracted obligation to the depositors vs the uncertain returns on the financing (income) which may result in the income is insufficient to meet the obligations to the depositors. For example, the commitment for Islamic Fixed Deposit is 4% (contractual) but the Financing portfolio into which the Fixed Deposits is deployed into only earns 3% (actual returns). Therefore, the 1% shortage is the DCR where the Bank will have to flow 1% of income from other portfolio to meet the deposit obligation of 4%.

SHARIAH RISKS – Risks arising to non-compliance of Shariah decisions and Shariah instructions.

- Shariah Compliance Risks – The operation of an Islamic Bank is hugely dependent on the requirements of the Shariah Committee and approvals obtain on the process and procedure. Inability to comply with Shariah requirements puts the operations of the Islamic bank at risk as the department may be regarded as non-Shariah compliant business.

- Fiduciary / Ownership Risks – Some of the structures under Islamic contract requires the bank to operate outside the scope of a financial intermediary. It requires the bank to hold property or trade commodities or own and lease assets, with various contracts using various roles and responsibilities. The risk of multiple roles and function must be clearly defined and implemented.

- Regulatory / Reputational Risks – Changes in regulations requires quick adaptation to ensure compliance to regulation and maintaining the banking reputation intact.?

SO HOW DO YOU MANAGE ISLAMIC RISKS AND SHARIAH RISKS

As mentioned, Islamic management of risks should not be any different for the base of conventional bank’s methodology of measuring risks. There must be deep understanding of the products and structure for the bank to be able to assess the risks associated. To manage an Islamic Bank and its risks, the bank must first identify each of the risks and form safeguards to settle the above. Then only an Islamic bank can formulate suitable controls to ensure the Shariah specific processes and Shariah pronouncements are being monitored and implemented with sufficient support (internal or external). Wallahualam.

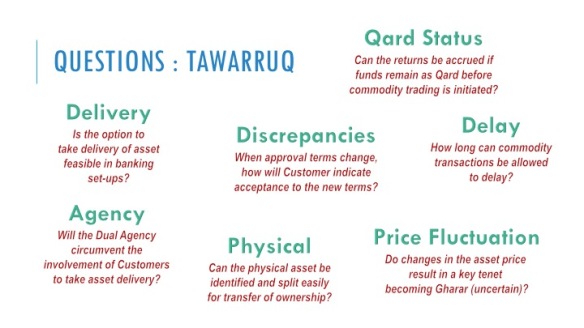

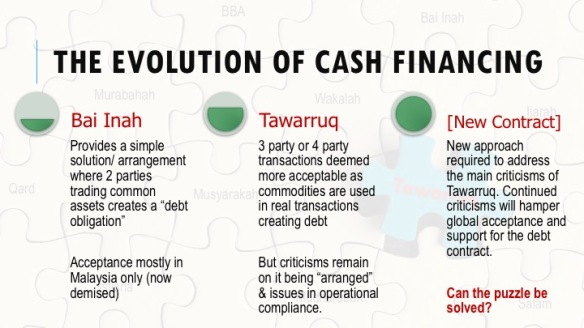

EXCERPT : In ‘Islamic’ Banking, we dance around issues as if vying for a Bollywood Oscar. The latest theme, on ‘Sustainability’, is fashioned after the United Nations (UN)’ Sustainability Development Goals (SDG), in concert with other large organisations such as the Islamic Development Bank and the World Bank. While they may seem like a natural fit with goals such as peace, justice and decent work for all, a closer look uncovers a few fundamental flaws. Firstly, while championing social and environmental wellness, we continue to evade the main issue, which is that profit- and loss-sharing, arguably the main tenets of Islamic Banking, have been replaced with tawarruq, which resembles riba in form and spirit. Secondly, and related to the first argument, this concept of ‘Sustainability’ is at odds with the modern financial system. One is about preserving for future generations while the other belies a winner-takes-all mentality. There is a view that like Islamic Banking, ‘Sustainability’ cannot be sustained in Commercial Banks even though several of them, from Singapore to London, have adopted the practices. In Islamic Banks’ (blind) pursuit of Commercial Banking, are we being set up for failure?

EXCERPT : In ‘Islamic’ Banking, we dance around issues as if vying for a Bollywood Oscar. The latest theme, on ‘Sustainability’, is fashioned after the United Nations (UN)’ Sustainability Development Goals (SDG), in concert with other large organisations such as the Islamic Development Bank and the World Bank. While they may seem like a natural fit with goals such as peace, justice and decent work for all, a closer look uncovers a few fundamental flaws. Firstly, while championing social and environmental wellness, we continue to evade the main issue, which is that profit- and loss-sharing, arguably the main tenets of Islamic Banking, have been replaced with tawarruq, which resembles riba in form and spirit. Secondly, and related to the first argument, this concept of ‘Sustainability’ is at odds with the modern financial system. One is about preserving for future generations while the other belies a winner-takes-all mentality. There is a view that like Islamic Banking, ‘Sustainability’ cannot be sustained in Commercial Banks even though several of them, from Singapore to London, have adopted the practices. In Islamic Banks’ (blind) pursuit of Commercial Banking, are we being set up for failure?